Ignorant of Our Ignorance

We often think of Jesus healing the blind. But how often do we remember that he also came into the world to blind those who see? “For judgment I have come into this world, so that the blind will see and those who see will become blind” (John 9:39-41).

How do “those who see” become blind? Easier than we might imagine. The conscience is to the soul what the eyes are to the body. Proper eyesight makes us aware of the world in which we live. Acting as a lens, a good conscience also makes self-aware by judging whether we are perfecting the image of God in us. It’s how those who are blind come to see.

That’s why scripture cites the Apostle Paul and David as exemplars of good conscience. Their conscience was a lens helping them “see” that they were blind, so they came to see.

Now a lens can warp, so our conscience can warp. So you may imagine that, when I say things like, ‘a good conscience makes us self-aware,’ that I am saying people of warped conscience are self-unaware. You would be right. They think they see, but they’re blind.

There are a number of reasons for this. The first is how the interior conscience aligns with the left brain’s hemisphere which concerns itself with sorting and categorizing information inside our head. This makes the left hemisphere much less aware of what’s outside and beyond our head than the right hemisphere. The left hemisphere “sees less in all senses,” writes Iain McGilchrist, yet it “does not seem to know what it is it does not know.”

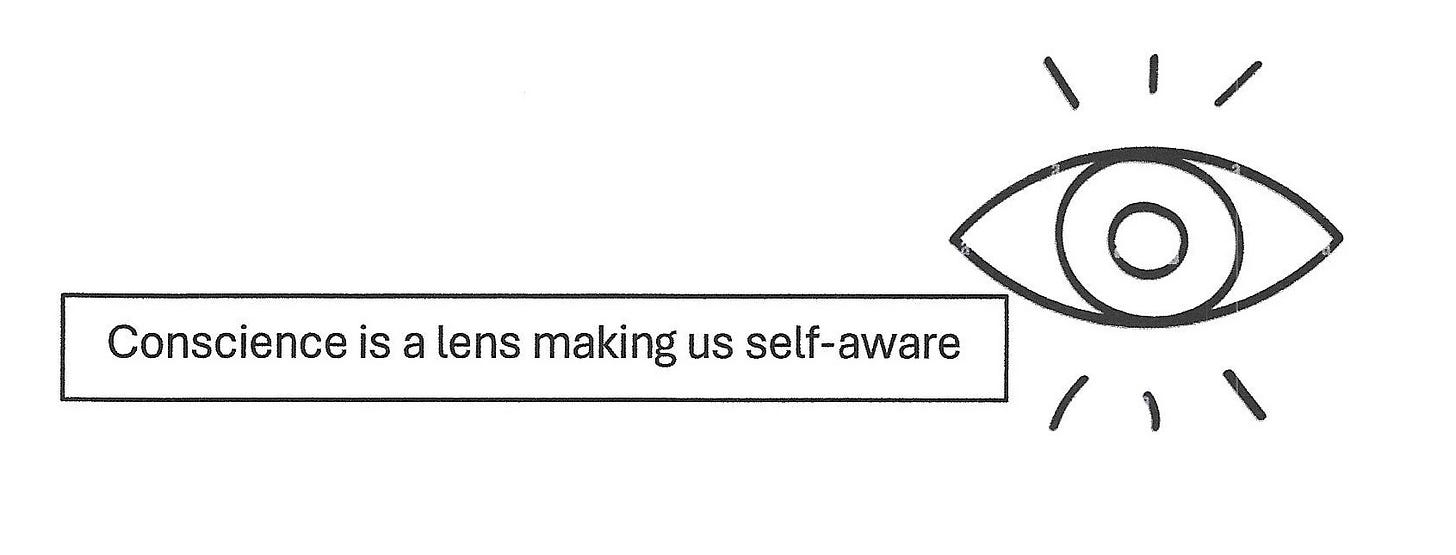

We can see this in a neurological condition referred to as left neglect. After damage to the right side of their brain, many stroke and brain-injury survivors are left with this type of attention deficit—and are often not aware of it. For instance, when shown drawings of a clock, house, and cat (left-hand column), those with left neglect usually draw what we see below (on the right column).

There’s obviously a lot they’re missing.

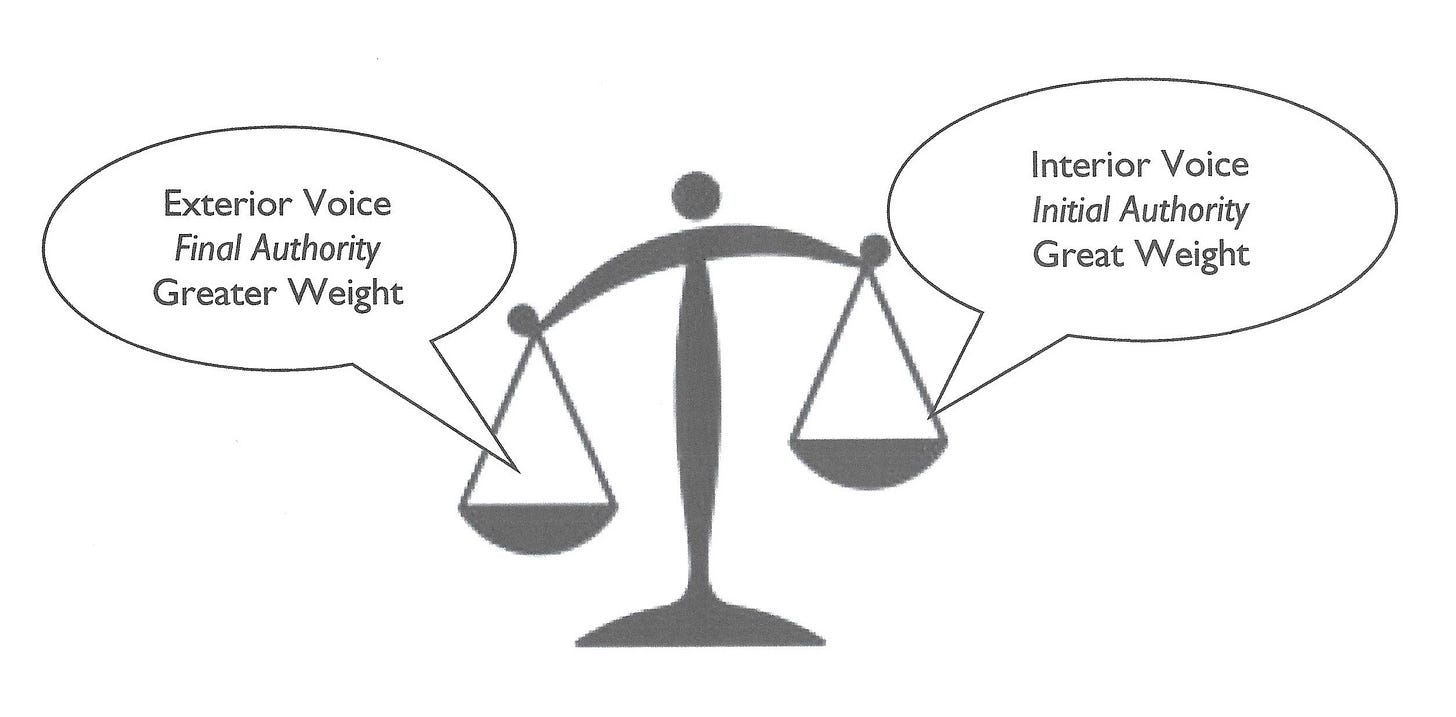

By contrast, the exterior conscience aligns with the brain’s right hemisphere which concerns itself with the world outside and beyond our head. The right hemisphere has an intuitive sense that its drawings, which tend to more complete, are still missing some elements, even when they’re entirely right. When we give greater weight to the exterior conscience; that is, we bias the right hemisphere, we look for “the Other” (as McGilchrist calls it) hemisphere, the left hemisphere, for whatever help it might offer the right.

The problem is that the left hemisphere doesn’t look to the right for help when the interior conscience is given greater weight. “It thinks it knows it all,” writes McGilchrist, “while it cannot be aware of what the right hemisphere knows. Each needs the other, but the left hemisphere is more dependent on the right than the right is on the left. Yet it thinks exactly the opposite and believes that it can ‘go it alone.’”[1]

In other words, when our interior conscience is the greater weight, the left hemisphere thinks it sees, so we give it greater weight. We in fact become blind.

McGilchrist says 95 percent of the western world’s population biases the left hemisphere. This means it’s blind, which “explains the predicament we find ourselves in today.” How then do we redress the balance between the brain hemispheres? McGilchrist suggests you ask yourself: What does my particular take on reality exclude from my vision? He suggests this warning that “it’s not ignorance, but ignorance of ignorance, that’s the death of knowledge.”

Another way we can redress the balance between the brain hemispheres is to look at how scripture depicts the damage done by those with a warped conscience. There are three types of warped conscience in scripture, and next week we’ll begin unpacking one a week.

[1] Iain McGilchrist, Ways of Attending: How Our Divided Brain Constructs the World, (Routledge, 2018)